Research and significant finds

The archaeological site in Chotěbuz-Pododora has intrigued historians and archaeologists since as early as in the 19th century, yet the first excavation was made as late as just before WWI. Some site testing was done in the 1930s. The first professional-grade research was conducted in 1952 and 1954 under the supervision of Lumír Jisl.

However, the long research period culminated in systematic scientific on-site research starting in 1978, conducted by Pavel Kouřil, then researcher and presently director of the Archaeological Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic in Brno.

Archaeologists come to the hillfort every year. Thus the site, known as the early mediaeval fortified promontory settlement in Chotěbuz-Podobora, is one of the most well explored and documented archaeological sites in the Czech Republic.

Significant Chotěbuz finds

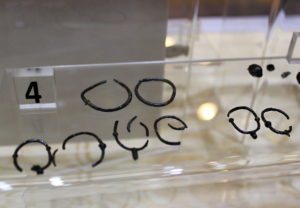

Hallstatt iron bracelets

There are about 14 iron bracelets dating back to the Hallstatt era in the Czech part of Silesia. Two of them were found in the Chotěbuz-Podobora hillfort. One of them is a simple iron C-shaped bracelet.

The other one is more impressive immediately at first glance: it’s a rather massive iron circle with seal ends overlaid one over the other. This is an instance of iron used as jewellery, right in the early stages of iron production in our country. Judging from analogical finds, both bracelets are estimated to date from between 750 and 550 BC.

Handcuffs

Iron handcuffs are a less common part of the metallurgical inventory of the sites within the hillfort. The Chotěbuz item is a distinct well-preserved showcase. One cannot come up with a clear definition of its purpose, yet with some caution, this could be proof of the slave trade in the Slavic society, as hinted at in written sources and by analogical finds from other sites. Another option is the use on cattle feet or other purposes not related to slave keeping.

Riding equipment

Several items of riding equipment originate from the Chotěbuz-Podobora site. They include a disk spur (spur attached to a boot using a disk and rivets) and a massive stirrup with a dented tread, triangular sides and high branches.

The buckles found may also form part of riding equipment or a horse harness. Unlike this, a well-preserved iron bridle-bit is undoubtedly part of a horse harness. The items, in particular the spurs and stirrups, are telling proof of the elite residing in the Chotěbuz- Podobora hillfort.

A greyhound bone and bones of a Hallstatt era man

Two instances of hillfort finds, combined with scientific analyses, allowed us to uncover a specific “story”, a rare feat in terms of archaeology.

The first instance is the skeleton of a man from the Hallstatt era. Strontium analysis showed he was most likely born somewhere else and moved to Chotěbuz-Podobora in his early adulthood. Most likely, he spent his last ten years in the Baltics, was well fed, and part of the privileged class. However, he died a violent death, aged 30-40, apparently during a war event taking place in the hillfort in the Early Iron Age.

Skeletal remains are the starting point of another story, this time from the early Middle Ages. Several bones of an unusually large dog were found in the acropolis zone. Analyses identified the breed to be a Polish Pointer or greyhound, which were dog breeds rather uncommon for Slavs at the time. Strontium analysis indicates the dog was born somewhere in central Poland or the Baltics. So perhaps this dog was an exclusive item owned by a member of local elite, acquired through a deal across a long distance.

Penny and other proofs of trade

Among the finds relating to trade, the silver denier or penny of Hungarian king Stephen I (997-1038) should first be mentioned. The coin is assumed to have gone into circulation (and thus, to the hillfort) not before the 1020s, more likely at some point in the 1030s or 1040s.

The coin is significant not just as proof of contacts with Hungary, but it also implies the time when the active settlement was discontinued, in approximately the mid-11th century.

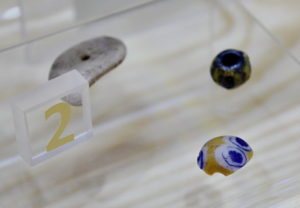

Other items to be listed are a bead of black glass paste with a double white line, dating back to roughly the 11th century. This type is rare in this country, with counterparts in the Carpathian Basin and at some sites in Poland.

Another remarkable finding, relating to Eastern Europe, is a blade-shaped key, probably fitting a spring suspension lock. An item imported beyond any doubt is a two-cone spindle whorl made from Ovruch shale, a stone usually associated with trade with Kievan Rus. Similar items found in this country come from sites located along the main trading routes. The presence of lead also hints at trade: a nicked mane coin and small lead rolls, likely obtained through contacts with Dąbrowa Górnicza (next to modern Katowice), a site where lead was mined and processed.

Great Moravian Imports

Both the spur and stirrup are likely to be of Great Moravian origin. Militaria include “bradatice” axes, typical weapons of Great Moravian warriors.

Another category of finds is jewellery, specifically earrings, hinting at South Moravian origin. 12-15 pieces of such earrings were found. They can be attributed to the Danubian type of jewellery, with some opulent items matching the Veligrad type. The material used was mostly silver-plated bronze (with some items of pure silver), but the entire set is very burnt. In terms of type, there are earrings with a lower arch decorated with filigree wire, earrings with a hollow cylinder pendant, with a roll-shaped indented pendant, as well as simple grape-shaped earrings and simple rings.

Analogies are also found at other Silesian sites, yet undoubtedly the entire art style of the jewels is of Great Moravian origin, so they are imported items rather than local products based on Great Moravian traditions.

Agricultural production in the hillfort

The Chotěbuz-Podobora hillfort shows a variety of finds related to agriculture and agricultural production, allowing to us conclude the settlement was self-sufficient in terms of food. Most people seem to have been involved in agriculture, in close proximity to the hillfort. The items found cover the entire production process.

A great many remains of stored crops were found on the site, in particular charred grains of many cereals. The iron plough blade found implies field cultivation, white iron sickles relate to harvesting. The harvested grain could then be brought to roasting vessels; a unique Slavic type of vessel reminiscent of roasting pans was used to roast the grain, most often unripe. Some roasting vessels found in the hillfort are surprisingly big, hinting at large-scale agricultural production.

The other grain processing option proved by the finds is grain grinding to obtain flour. A number of quern-stones (manual grinders made of stone) were found on site. The quern-stone consists of a flat static stone and a movable stone, with both types (chiselled in a slightly convex shape) found in a range of sizes. Additional quern-stone pieces were found that had remained unfinished.

Animal breeding is attested by bones found, sheep shears and structures identified as probable stables.

Proof of hillfort destruction

Throughout its history, the hillfort was destroyed several times in military actions. The destruction is clearly confirmed by finds from a fire layer: alongside the earthworks, some logs that were part of the wooden fortifications were found partly burnt (and thus, partly preserved).

The defunct artisan and residential structures contain objects that imply they were damaged by collapsing roofs. But the finds also include animal remains: as if the residents took shelter and the animal remained trapped in burning and collapsing buildings. Thus, a destroyed structure assumed to have been a stable contained the skeletons of a pregnant cow, pig, three sheep and a dog. The war events are also documented by military items, in particular arrowheads, and judging from the state and position of some, featuring traces of use when the palisade was stormed.

By Petr Zajíček